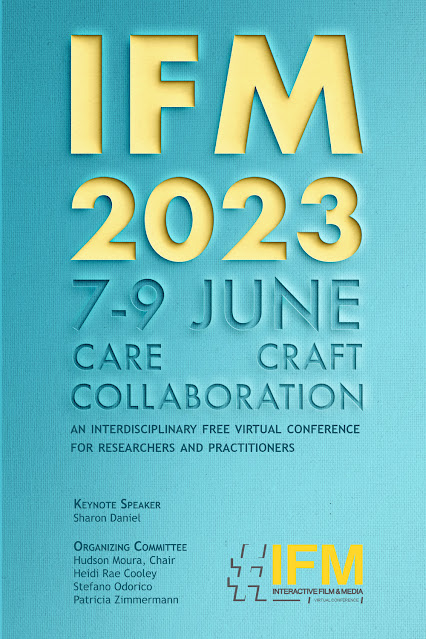

Call for Papers for IFM Annual Conference

June 7-9, 2023

Craft, Care, Collaboration

Deadline: January 9th, 2023

EXTENDED Deadline: Monday, January 30th, 2023

The annual Interactive Film and Media Conference invites abstracts that explore, interrogate, interweave, unravel, and reinvent the dynamic relationships between craft, care, and collaboration across new media platforms, practices, and theories. This nexus of craft, care, and collaboration has emerged as a fertile ground for thinking through the crucial yet unresolved work of combatting polarization with multiple voices, plural practices, and new ways of working together to invent shared languages and ideas. The conference invites participants to think about these three axes–craft, care, collaboration–whose definitions and relationships are not fixed, but fluid and adaptive.

CRAFT

Craft suggests a physical relationship to material to emphasize tactility and concrete engagement with the matter of the world. Craft traditions such as quilting bees and barn-raisings, gardening and sewing, etc., re-emerge in digital cultures through questions of tactility, working with machines, rethinking exhibition strategies, and more. Sometimes, craft is considered as a form of individual authorship or artisanal; other times, it is deemed collective; most of the time, it winds between both. Our conference asks the following: what is craft? Why is it important now? Is it possible to think of craft in new ways? How does craft work through our engagement with material?

CARE

Care implies attention to relationships between the human and the nonhuman. It is embedded in the relationship between makers/designers and subjects, and between work(s) and its participants/audience. This notion speaks to the affordances of the technologies, materials, and infrastructure that make media work possible. Care pays attention to how work is made in communities, and how an ethics of care entails endlessly reformulated and adaptive relations that we inhabit. How do works invite care? What is the ongoing work of care in media work and practice? What kinds of bonds are formed in and through this work, and how can they be nurtured, respected, and encouraged to evolve?

COLLABORATION

Collaboration has become a dominant meme in media practice and scholarly work. It opens up ways to think beyond the auteur-as-individual, drawing on long traditions across the arts and platforms of working with others. It moves from the one to the many, from the monovocal to the polyvocal. It is often grouped with concepts such as collectivity, community, co-creation, participatory modes, activism. What is collaboration? How does collaboration change from project to project in different iterations and different political, social contexts? Why is collaboration necessary or important? What challenges and pitfalls does collaboration pose?

This conference does not propose closed definitions of the terms craft, care, and collaboration. Nor does it map the ways in which these three terms entangle, enmesh, separate, collide. Instead, the conference celebrates the open fields, gaps, and fissures between these terms in an initial attempt to enhance what is ambiguous, unresolved, and needing our attention. The conference invites participants to think through and imagine craft, care, and collaboration in new ways that mine these cracks and ambiguities.

KEYNOTE SPEAKER

Sharon Daniel, University of California, Santa Cruz

Daniel's work is located at the nexus of art and activism, theory and practice. She is a professor and media artist who creates interactive and participatory documentary artworks, innovative online interfaces, and multi-media installations addressing social, racial and environmental injustice issues. Her work has been exhibited in museums and festivals internationally, and her essays have been published in books and journals. Daniel was honored by prestigious awards, scholarships, and grants worldwide. She is a Professor in the Film and Digital Media Department and the Digital Arts and New Media MFA program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she teaches digital media theory and practice classes. Her recent project, Exposed, an interactive documentary, which provides a cumulative public record and evolving history of the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on incarcerated people, was presented at the #IFM2021 Conference and published in the proceedings.

The 5th Interactive Film and Media Virtual Conference (June 7-9) invites academics (faculty, researchers, and Ph.D. students) and practitioners (filmmakers, artists, VR and game designers, and media producers) to submit their paper abstracts. While presenters are encouraged to consider the themes of Craft Care Collaboration. Proposals on matters relevant to the IFM community and beyond are welcome.

FULL FREE ADMISSION

No fee is charged for presentation and attendance at this conference or publication at the journal.

PAPER ABSTRACT SUBMISSION

To submit your abstract (500 words long, including the research objectives, theoretical framework, methodology, and hypotheses) and a brief Bio-CV (150-200 words), please download the paper proposal application form here:

IFM2023_Paper_Presentation_Proposal.docx and submit it to the section ‘conference paper abstract’ at the #IFM Journal’s Submissions system by the deadline.

RESEARCH CREATION SUBMISSION

For Research Creation and Artist/Collective Projects Interactive Workshop proposals, fill out the form, including the research creation’s description, research objectives, theoretical framework and methodology, and a brief Bio-CV (150-200 words for each participant/author). Please download the research-creation presentation proposal application form here: IFM2023 Research Creation Presentation Application Form.docx and submit it to the section ‘ research-creation presentation’ at the #IFM Journal’s Submissions system by the deadline.To guarantee presenters' full engagement and interaction during the workshop discussions, the organizers will provide an online training session before the Conference.

PUBLICATIONS & PROCEEDINGS

The video presentations and the peer-reviewed post-conference papers will be published in the #IFM Journal.

KEY AREAS

1. Digital theory: history, storytelling, intermediality, transmedia, multimedia

2. Interactive film: documentary, fiction, animation

3. Interactive platforms: teleconference, streaming, mobile screens, virtual museums, multimedia installations

4. Interactive media: webseries, digital news, snack media, ecomedia, social media

5. Games: storytelling, education, docugames, serious games, games for change

6. VR (Virtual Reality) / AR (Augmented Reality): immersion, alternative environments and realities, interfaces

7. Database and Big data: archive, politics, ethics

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE

Hudson Moura, Chair (Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada)

Heidi Rae Cooley (The University of Texas at Dallas, USA)

Stefano Odorico (Technological University of the Shannon, Ireland and Leeds Trinity University, UK)

Patricia Zimmermann (Ithaca College, USA)

More info: https://journals.library.ryerson.ca/index.php/InteractiveFilmMedia/IFM2023

Contact email: ifmjournal@torontomu.ca